I was once introduced to a new colleague who made very direct, sustained eye contact, and I thought to myself as I spoke with him: he's on track to be in admin. He just seemed the type to make connections and get ahead and would likely end up at the board office. But then, after talking to him a few more times and seeing him in moments of awkwardness, I thought, "Oh, he's autistic." That didn't change my reaction to him at all, of course, but it did help me figure something out.

That interaction was a lightbulb moment that helped me understand the many many times someone gloms on to me as if somehow I'm the most interesting person in the room, then, after a few conversations in which nothing appears to go wrong, they completely ghost me. They thought, because of my sustained eye contact boring into them, that I must be someone important, an alpha even. Then they figured out their error and shunned me, embarrassed by their own mistake. I'm fine with someone changing their mind about hanging out because that happens to the best of us, but the absolute worst part of it, worse that literally being pointed and laughed at by other adults, is when they suddenly understand that I'm on the spectrum and start talking to me like I'm a flippin' space cadet.

So, just last month you wanted to take me to lunch at some fancy place, and now you've concluded that I'm practically brain dead. Curious. It's always startling how abrupt that transition is for people. And how reliable.

Then mix that in with "you can only do that because you're autistic" like writing every day, which is a thing that writers do, but if you can't motivate yourself to do it, then the reason I can do it despite clearly being inferior to you must be my hidden superpower of being autistic. So things I can't easily do are laughed at openly and the things I can do are discounted. Lovely.

It's not tragic, but it is trying. These little things can eat away at people. Surely we know it's not right to behave this way with others, though, right??

A few studies show that people notice something different about people with autism in the first few seconds of an encounter (h/t Callum Stephen). In one study (Sasson et al, 2017), they filmed a variety of people, some with ASD (level 1) and some neurotypical (NT), in a 60 second mock audition. The study participants were assigned to one of five groups to watch the videos and assess each candidate on likability, intelligence, attractiveness, trustworthiness, etc.: audio only, visual only, audio-visual, static image, and transcript. Only in the transcript option were people with ASD rated as highly as NT interviews. Even the still image set them apart. (Is that why there are no good photos of me: Internalized ableism??) The study concluded,

"First impressions of individuals with ASD . . . are not only far less favorable across a range of trait judgments compared to controls, but also are associated with reduced intentions to pursue social interaction [i.e. people don't want to talk to them]. These patterns are remarkably robust, occur within seconds, do not change with increased exposure, and persist across both child and adult age groups. However, these biases disappear when impressions are based on conversational content lacking audio-visual cues [in the transcript group], suggesting that style, not substance, drives negative impressions of ASD."

Thank the internet gods for allowing me some form of communication wherein I am not written off quite so quickly!!

They conclude that people notice differences in facial expressivity, eye contact, rates or timing of gestures, acknowledgement of personal space, and vocal intonation.

No kidding.

A second study (DeBrabander et al., 2019) had NT adults rate videotapes of interviews: half the interviews were of people with ASD and half NT. The participants indicated their interest in interacting with them in the future. The treatment/control in this one: half the participants were told about the ASD diagnosis of those specific interviews, and the other half just watched them all without this knowledge. Their finding was similar to the previous study when people weren't told of the diagnosis, BUT first impressions improved when NT adults were made aware that the candidates had ASD.

What we don't know from this study is if they said they'd hang out with them from a do-gooder sense of pity and then would have talked to them like they're flippin' children!

Finally, in a 2014 study, Ruth Grossman showed NT people videos of children with and without autism, and it only took ONE SECOND of tape to realize something was different about the ASD kids. She tried to find the specific movements and gestures that were the give-aways by using motion-capture technology, and found less symmetry in facial expressions. She's currently studying the timing of words and gestures as well.

I've been told repeatedly by well-meaning people that I shouldn't care what people think of me, and I don't for the most part, but this isn't just a social isolation issue. This affects the ability for people on the spectrum to get jobs or be approved for apartments, or even to get help in a store. It's a human rights issue if an identifiable group of people are instantly disliked by the general NT population.

On the one hand, it's validating to know that I'm not just being paranoid. On the other, this is really shitty. This is my children's experience as well. Grown-ass adults look at these subtle differences and decide, after a few seconds, this is not someone I'd be willing to sit beside, much less hang out with.

Callum Stephen wrote about the loneliness that comes with autism, but it's not from the condition itself, but from,

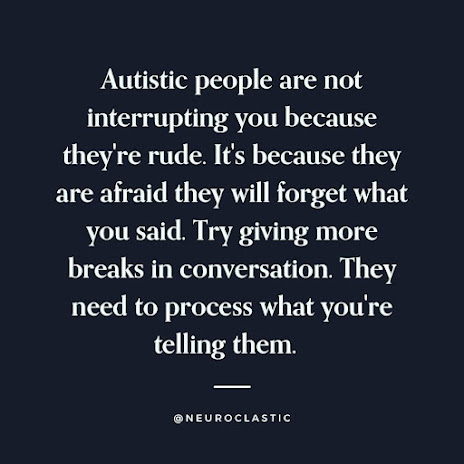

"society not being aware of our differences; not understanding why we may communicate and behave as we do; not accepting why we may need to approach life differently; not meeting us halfway and accommodating our differences as much as we accommodate theirs."

Of course suicide and self-harm levels are higher for people on the spectrum, as cited in a recent study (Lai et al., 2023), 25% of people with ASD experience suicidal ideation. They cite the greater likelihood of a psychiatric diagnosis (mainly anxiety and/or depression) as relevant to the increased rate of suicide, and call for greater diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders. Unfortunately they didn't ask about the participants' experiences with larger society or look into the effect that being shunned by others repeated throughout your life might have on the likelihood of developing anxiety or depression.

To be fair, some people with ASD can be annoying - I know I can - but that's not why these studies found they're being disliked. It's entirely based on first impression. It has nothing to do with thirty minute info dumping without a breath or incredible honesty when asked "How do I look?" or the several minutes of silent thinking time sometimes required to answer a straightforward question.

It also makes me think back to those three years I spend on dating sites and the number of times I sat alone waiting for someone who didn't show up. My son said, "It's because you're so awkward" (yup, honest to a fault), but I countered that it couldn't be the case since they hadn't had a chance to see just how awkward I could be yet. But turns how he was right; it was the awkwardness! It was my asymmetrical facial expression and posture and gaze as I sat quietly waiting, sipping a drink, actually thinking I might look good.

I'd like to propose promoting our perception of people who are ASD, ADHD, and NT as each being from a different culture. NTs just happen to be the dominant culture that the rest of us are hoping will accept us in a cultural mosaic way, instead of in an assimilationist way.

When people tell someone they can only write quickly because of ASD, that's like discounting someone's skills by saying they can only play soccer well because of where they were born. Openly making fun of someone stammering to get out their idea and losing all train of thought when interrupted is like openly making fun of someone struggling with English as a second language. Talking to people with ASD like they're children is like talking to people with an accent like they're children.

The only problem with this approach, of course, is that people do make fun of people and discount them for racist or bigoted reasons. But our anti-racism work seems to be getting further than our anti-ablest work, so maybe this can help a few people to begin to hear themselves differently. If you're meeting someone from a dating app, and they're eating food you don't recognize or wearing clothes that don't fit current local fashions or they're otherwise just different, somehow it's better that it's because they're not from here. That's because we know we can learn about one another's culture and adapt. That's still the case with the ASD and ADHD in the crowd.

No comments:

Post a Comment