We've got marches and rallies surfacing, sometimes right outside of schools, with people chanting, "Leave the kids alone" in order to put an end to "gender ideology."

What does this even mean?

First off, check out this 8 minute TikTok on indoctrinating kids (also here if embedding doesn't work):

@headonfirepod Replying to @Katie ♬ original sound - Don Martin

"I was just a kid trying to be a kid but your kids wouldn't let me."

On one side is the belief that people like Don Martin need to be protected from harassment and assault that might come from other children (and adults) who don't understand that people can be different yet equal to us. We're no better or worse than one another because of our interests, or our clothing, or who we date. But on the other side, there's a belief that the children are right to do everything to let him know that he's not living the right way. They're saving him, and no teacher should intervene to indoctrinate children in that first belief, as if that kind of difference is in any way acceptable.

So, which belief system is an ideology, what does that even mean, and how can we sort our which is the better system?

I'm going to get into the weeds here for a bit, but then I'll come to the issue further down.

ON IDEOLOGY

One of the best explanations for ideology comes from a fantastic read, Religion at Ground Zero, by Christopher Craig Brittain, the Dean of Divinity at Trinity College in Toronto, and I hope I do it justice here. The book is about, in part, how religion is used to manipulate the masses in the worst sort of ways after catastrophes.

I had always used the term "ideology" to mean a belief based on a cultural understanding of the world shared with a set group of people - sort of an implicit bias writ large that is a concern because it can colour our perception and prevents us from seeing things clearly, a worldview that influences our opinions on things. And it is that, but there's more. Brittain uses a quilt analogy.

Words are symbolic and none exist in isolation; all concepts are relative to and contrasted by other concepts to develop meaning for us. And we use various concepts to understand the world, like sewing a quilt: the different squares can look different depending what they're attached to. I love this metaphor because we're only just getting into it, but already we can get that a light blue changes hue depending if it's beside a teal or violet piece. Then, because words are just symbols that represent ideas, nothing is ever perfectly clear and certain. Something's always left out. "Our quilt will always have a few holes in it," places where squares are missing or torn, where there's a gap in our knowledge or understanding. So 'the Real' (as Lacan puts it), or maybe the Truth, (with a capital 'T' to indicate it's universal and solid) includes all these holes in our quilt - and all the things that are outside our realm of language. We can know things that are true, but never get to the Truth of the matter. Most people hate the uncertainty of things, so they rush to fill in all the gap with stuff that isn't quite right with something that can tie it all together even though we can often (but not always) feel that we're fudging things. It's like patching the holes of a silk quilt with polyester. The more we patch over the holes to develop some certainty for ourselves in the world, the further we get from Truth. Our certainty is mistaken, no matter how much it can feel right - or how much we convince ourselves it's right.

The patches are our ideologies. In hindsight, we might realize how ridiculous it was for anyone to believe it, but at the time it does such a good job of unifying our ideas and holding our belief system together that we overlook that it doesn't quite make sense. The example Brittain uses is the Nazi concept of "the Jew" which held together contradictory ideas by,

"serving to represent all the grievances and frustrations of a nation experiencing tremendous economic and political disruption. This scapegoat concept enabled many to continue to trust and celebrate their idea of 'the German people,' because the cultural quilt was held together by the idea that the 'Jews' were to blame for all their problems."

We fall into this way of thinking because the Real is elusive; we'll never know certainty or have perfect knowledge, and we need to come to terms with that. He explains philosopher Slavoj Zizek's position. He refers to The Matrix when he gets into this, which is an illustration of Plato's Allegory of the Cave. Are we going to choose ignorance, living our lives in the cave, forgetting all the inner workings of the world by distracting ourselves with cars, steaks, and blondes, or are we going to choose wisdom, leave the cave, and try to get our heads around it all, try to really see things as they are? Zizek says many people take an even worse option with a "fake passion for the Real": they stay in the cave with all the distractions but think they understand it all. He calls it "the ultimate stratagem to avoid confronting the Real."

We do this over and over because as soon as we glimpse how things really are, we realize it's way more complicated and uncomfortable than the discomfort from not having certainty in the first place! We don't really want to know, we just love that finished feeling of having it all figured out. We want a solid sense of the world we live in and an easy way to understand the people we encounter.

How do we avoid ideology when our knowledge is necessarily incomplete and embedded in ideological structures? We recognize that "no solid ground of knowledge exists to stabilize and perfect the world . . . accept the world as it is . . . to avoid violent or aggressive attempts to patch the hole." Beliefs are always the product of a leap. Brittain criticizes this perspective, though, as "it makes a virtue out of a problem" potentially giving license to act without providing justification. It starts leaning towards nihilism. (Nolen Goertz's definition: "Nihilism is about evading reality rather than confronting it.") Brittain turns to Camus's The Plague (bit of a summary here) to explain his concern with those "who employ their own distrust of the status quo as an excuse for absolutism and an unwillingness to compromise."

The lines that stays with me from The Plague, and it fits here as well, is when Camus's main character said, "Man can't cure and know at the same time. So let's cure as quickly as we can. That's the more urgent job." It's impossible to look predicaments, pestilence, and death in the face and also act. It takes our breath away and saps our energy, making our knees weak with the recognition of it, so we set aside knowing in order to get things done. Camus separates those lost in "everydayness" (in the cave) in large scale denial with those who understand and face the absurd (leave the cave) to see the reality of the social order, the futility of hoping to solve it, and the need to accept our situation with solidarity and face that we have to act, to revolt, while forever balancing the needs of individuals and society. Nobody's coming to save us, and nobody's responsible for this absurdity. It just is. If we can see it, and accept it, then we can have a collective response to it. Camus writes, "There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise." We keep thinking bad things won't happen as if we somehow expect to be protected. The plague is the poisonous ideology of the Nazi regime that tries to destroy citizens, which left "traces in people's hearts" waiting to be re-awakened. Absolutely! Solidarity's victory is fragile. "He knew that the tale he had to tell could not be one of a final victory. It could be only the record of what had had to be done, and what assuredly would have to be done again in the never ending fight against terror. . . . Joy is always imperiled."

The part of Camus that Brittain points out: "They forgot to be modest, that was all, and thought that everything still was possible for them; which presupposed that pestilences were impossible." People become too self-important to be able to act. It's Rousseau's perfectibility that keeps us from acting collectively, despite the reality that, according to Camus, we can't be happy alone. Only when we move out of ignorance can we develop concern for others.

We must try to be very careful not to get caught up in any stereotypes about who people are and avoid any sweeping generalizations about entire concepts like religion is oppressive. Brittain uses the example after 9/11 when both bin Laden and Bush insisted they're keeping people safe from enemies. There was a dichotomy of beliefs between America was victimized by evil terrorists and America got what it deserved for exploiting areas, but neither are true. Both sides have evil, and both side have victims. Brittain says, "Rather than calculate which side had been the most victimized, 'the only appropriate stance is unconditional solidarity with all victims'."

This fake passion for the Real is insincere, or at the very least an incomplete attempt to understand and fix a problem. It can be easy to get caught by it. It takes some thought to ensure we're not categorizing a group or a concept with too broad a brush, which is a start at undoing ideologies. Once we undo categorizations, and we start to see particulars, then we really see how much there is to know and how unwieldy it all is! Everything is much more complex and nuanced, and it's impossible to sort it all out without categories, but the categories are necessarily mistaken, offering false comfort.

Zizek says the way out is through the Radical Act, a Pascalean wager in which we follow an option that can't be proven to be successful from the get go, but is the better option. I did that type of calculation around Covid way back here about lockdowns and again here about masks to deduce when it will be better to act than to keep on doing what we're doing.

Brittain has a concern with Zizek getting too stuck in the system and brings it all back down to the ground: "Don't engage in 'radical Acts'! Help people!" There's a problem with focusing on revealing the cracks of injustice in our corrupt social order to the point that some will refuse to feed the hungry because that just serves the system. I've seen that in teaching when people argue that teachers shouldn't bring their own tech because it helps enable the government to successfully defund education. While I get that, like Brittain I lean towards doing everything to teach the best way possible -- to just feed the hungry who are in front of me and find other means to try to change the system that doesn't ignore or permit the immediate suffering of human beings for some larger cause. We can do both!

ON GENDER IDEOLOGY

So what's all this got to do with gender ideology and protests disrupting teaching??

There are several underlying ideologies informing the protesters that are obvious to me, the big ones being: the body God gave you is sacred, so all trans children are being mutilated, and man can only lie with woman. Of course other forms of health care that involve cutting into the body are not being protested in kind, and I already mentioned here all the problems with focusing on these bits while ignoring all the other rules. Some American protesters have signs with Luke 17:2 on it: "better to be thrown into the sea with a millstone tied around their neck than to cause one of these little ones to stumble." But they miss the flavour of just two verses over: "Even if they sin against you seven times in a day and seven times come back to you saying 'I repent,' you must forgive them."

Children being encouraged by their parents to stomp on rainbow flags perpetuates this ideology, hardcore. That protest provoked a Shelter in Place situation for the school, which makes it questionable if the protest is actually about the wellbeing of children in the first place.

But "gender ideology" is being used by protesters to discuss a different ideology that's being perpetuated at our schools: people can tell us their gender, and we must teach diversity and inclusion and loving one another no matter what they look like or who they love (more on where this may be coming from here).

We've got the Human Rights Code, the UN's Declaration of Human Rights, and the UN's Convention on the Rights of the Child on our side, and much of the Gospels lean this way too, but maybe we're all being sucked into a harmful ideology and unable to see clearly outside of it.

The unknowable bit that we're coving up in our quilt: the right way to raise children to be. So what is bad for children? What will cause them to stumble? Is it better to teach children to never judge others or is it better to teach them that there are wrong ways to be and to love?

Let's look at that Pascalean wager, granted this is necessarily informed by my own ideologies, and I have a lot of paisley and prism patches in my quilt:

If we teach kids not to judge others for who they are or what they wear or whom they love, and teach them that there are many different types of families, and love is what matters most, then the 2SLGBTQIA+ will feel valued and accepted, and they might express themselves with some clothes or jewelry or make-up that's less mainstream, but some straight cis kids will be exposed to people that are different and they might feel weird about that. One thing that's changed since the last time we had to fight for these rights like this back in the 1970s is the huge number of shows with characters and celebrities and just regular people who are out and proud. There are a ton of role models to show kids that it's not that weird to be 2SLGBTQIA+! (Provided they're allowed to watch them, that is - the more sheltered kids need school to teach them about the wide variety of people we have in this world.)

Alternatively, if we ban any discussion of sexual identity or orientation at school, and get rid of any books with stories of them, then 2SLGBTQIA+ kids might feel really uncomfortable about themselves, experience self-loathing, and may become suicidal. And the straight cis kids could leave school believing that it's acceptable to denigrate anyone different and harass people for being the wrong kind of person and stomp on symbols that are important to them, leading to a hate-fueled world.

I can't not see these as the two possibilities. Out of the four experiences, self-loathing and suicidality is the biggest risk. I'd rather have a few kids feel a little uncomfortable being near someone who looks different than a few kids hate themselves for who they are.

Zizek cautions, however, about how we view the "choice" in gender identity. It's not a free for all. We have to be careful not to get trapped by capitalist ideology that says we should do and have whatever we want without concern for the effect on others, for society. For capitalists, it's profitable for people to change who they are over and over, and an ongoing focus on the self identity is just another way of getting stuck in our perfectibility. But he explains that this is largely a straw man argument, presenting the situation as if it were all a game for people, when being ourselves is actually a very serious endeavour. Many protesters seem unduly concerned that schools are seeped in Sodom and Gomorrah orgies when they're really just trying to help kids understand and respect one another.

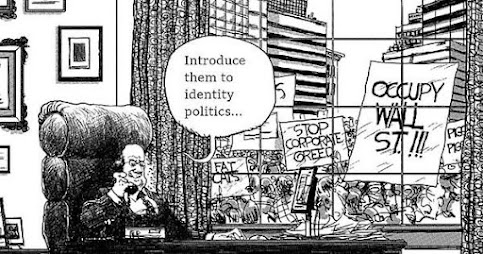

BUT, I can't help noticing that these protesters also tend to be people who rally against a whole host of things, like science, climate change, CRT, masks, and any sex education in the schools. It's not just a concern with 2SLGBTQIA+ kids. I think it's much more about using the concept of the "far-left" to, as Brittain says, "represent all the grievances and frustrations of a nation experiencing tremendous economic and political disruption." These issues are just scapegoats for rage about the difficulties of the world right now - a shortcut to provide a way to understand all things bad and a direction to focus their anger. Otherwise, if it's not the left that's to blame and rally against, then what else is there to do when kids are sick and medicine is in short supply, and suddenly we have to pay to get medical tests done that used to be free, and jobs are scarce and don't pay nearly enough to cover skyrocketing rent, which is out of this world!??

ETA: And then there's also this perspective:

Well, we have to find some solidarity if we hope to help one another through these years, which may be some of our very last as a species!

Lots of scientists are aghast at this graph today:

2 comments:

Watched movie Geronimo last night

Best line in movie

"Texans ...worst ... people ever"

Don Martin might agree

"Even if they sin against you seven times in a day and seven times come back to you saying 'I repent,' you must forgive them."

And if they don't come back saying "I repent" you are under no obligation to forgive them

And without recognition of sin , is forgiveness even possible?

It's a big question, and I think it depends on the offence. For many things we can forgive because they know not what they do. I wonder to what extent some people who are anti-mask/climate change/CRT, etc. have just read one to many questionable articles and don't understand how to sort science from bullshit, and are reasonably outraged given the information they believe. With a different source of information, they might be very different people, maybe outraged on the other side, the outrage being their disposition. I used to think, if I could just sit down and talk to them about it... But some misinformation runs too deep.

Post a Comment