We're skipping gleefully into the most absurd period in history.

The philosophical notion of the absurd came from Camus. It grew legs with existentialists after WWII when the youngest and fittest men were sent to be slaughtered in war. The streets of Paris were full of widows and grieving mothers and broken men. The question of the day was, How can we make sense of our lives and our place here and our idea of justice with all this going on?

I wrote more about it at length as I struggled with decisions foisted on me during my cancer years that left me with chronic issues. The answer from Camus is to stop trying to make sense of it all. Embrace the absurdity of our lives. We always have the option of leaving it behind, so if we choose to stay - famously if we choose coffee over suicide, then we have to acknowledge the world despite the weight of our knowledge pushing us to escape it through self-deception and cultural deception. All our choices are always a crap shoot, and at the same time, they're always our responsibility even though we can't possibly know how things will turn out, which, at the same time, takes the weight of that decision being the best choice off our shoulders. Outcomes are all out of our control, but we must try to do right anyway. We're taking a test without every having taken the course.

Instead of Why me?, we should ask, Why NOT me?. Instead of lamenting that things shouldn't be like this, we should think with a bemused curiosity: And now this interesting thing is happening! Something's going to happen next; why not this! The key is to avoid hiding from reality to see that things are random and we have little control but possible only some influence sometimes and yet are still responsible for whatever we do. Camus says,

"Crushing truths perish from being acknowledge. . . . The divorce between man and his life, the actor and his setting, is properly the feeling of absurdity."

How can I justify suggesting that the next few decades will be an even more absurd than after WWII? We're in a period or state of the absurd whenever we try to make sense of things and butt up against the lack of sense the world has to offer. From a distance of 80-some years, I can see the sense in doing everything possible to stop the Nazis taking over country after country. I think in 80 years, looking back, nobody will be able to make sense of allowing Nazi protests in the streets and Nazi affiliates hold public office. Nobody will be able to make sense of allowing a brain-invasive virus to run wild through our children. And, quite possibly, nobody will be there to try to make sense of things as climate change will force a collapse of civilization globally. But when we recognize the futility of life, but choose it anyway, and recognize that it's always a choice, then we are in the absurd, and it can offer glimpses of profound beauty and joy.

So I persist in trying to convince others to acknowledge what we're doing knowing it will not be nearly enough to affect anything because we are responsible for the choices we make each day as human beings with a rational faculty. But Covid could change how rational we are as a species.

Yesterday, biorisk consultant Conor Browne wrote,

Out of all the types of responses I receive on this platform every time I explain that I've never had Covid-19, the one that is - tragically - the most telling goes something like this: "Of course you've had it. Everyone has had it by now." There is often a tangible quality of simmering anger behind these types of responses, and I understand it. The anger is, I feel, subconsciously derived from the commenter perhaps realising that they have been sold a lie. Ever since Omicron emerged, a narrative took hold that simultaneously declared infection as inevitable and - most perniciously - that infection was beneficial ('hybrid immunity'). I know of plenty of people who deliberately 'got it over with' by dropping their own precautions and getting infected. Many of these people found out - sadly - that the use of the word, 'mild' in the medical lexicon is different from its use in common parlance. Simply put, they got much more acutely unwell than they were tacitly led to believe would be the case. Then they found out they could get infected again, and that 'getting it over with' was only temporary - basically, it wasn't 'over' This would anger me. Remember: infection is never inevitable. 'Mild' means 'not requiring hospitalisation.' Re-infection is the norm.

The frightening part of it is that anger without a guided direction. The premier is untouchable, so the closest target is that person walking down the street with a mask on. I've already been on the receiving end of that nonsense enough that I avoid the main streets in my city, which used to feel very safe to me. We will not be leaving this place gracefully.

|

| From here |

This existential way of thinking helps me to make peace with attending this week, virtually, a workshop on brain health in children in a room with scarcely a mask in sight, no other mitigations in place, and nothing mentioned about the potential risk people face from getting covid repeatedly. I had been kindly encouraged to come in person "after we finish eating" and to "just sit in a corner of the room" under the old-school belief that six feet of space is enough to stop an airborne virus. I find it heartbreaking how well-meaning yet misguided the suggestion is. Six feet made sense when we thought it was spreading through droplets. Now we know it travels like cigarette smoke and hangs around in the air. It's like asking someone who is deathly allergic to cigarette smoke to come in after we all finish smoking and just sit a little bit away from the rest of us. That change in information was never publicized sufficiently enough to get through to the general public.

If we stay on this trajectory, accepting the virus into our bodies, then future generations will have microclots as part of their "normal" vascular system. It will no longer be unusual. And strokes and heart attacks in teens and children will be just something we live with. And executive functioning -- the incredible working of the prefrontal cortex that enables us to sit and listen, plan ahead towards attainable goals, stay focused for extended periods, control emotional responses, and organize ourselves in a functional manner that is unique to human beings -- will become less effective, making learning strikingly more difficult. We're devolving. Classrooms may become chaotic and unmanageable, or even more so. Our ability to take responsibility - to have the ability to respond rather than just react - might also be lacking.

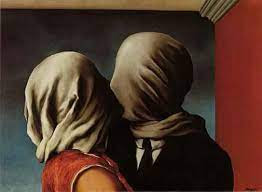

And it's not just children affected of course, but children will have no knowledge of it ever being any different. This virus is affecting the brains of lots of adults already, making many simple thinking tasks impossible for many who are screaming into the void for help. Sometimes I think that we may as well be drinking absinthe all day and wandering around in a stupor painting bizarre images - all unfinished. And yet a few of us "doomers" persist in trying to wake us all up to the reality:

Well, now this interesting thing is happening.

No comments:

Post a Comment