Jon Mooallem wrote a poignant piece in the New York Times yesterday about a project that's been recording people's experience with the pandemic since March 2020 over individual Zoom calls.

His words, "raise the possibility that when we say the pandemic is over, we are actually seeking permission to act like it never happened--to let ourselves off the hook from having to make sense of it or take seriously its continuing effects."

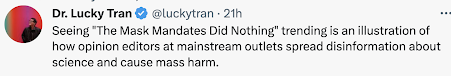

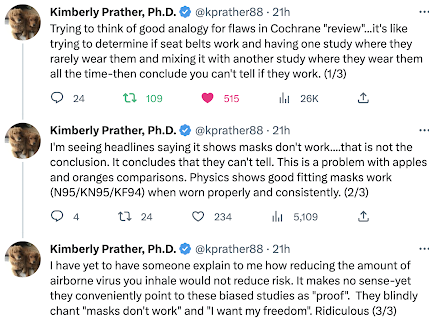

This is well-timed to butt up against the Cochrane Review, which said that wearing masks "probably makes little or no difference." It got slammed by many experts in the field explaining, once again, that random control trials aren't the end all and be all of scientific evidence (and here's a take-down of the lead author as well). Some Cochrane critics:

"It was all very idiosyncratic. Every life, every day, could be upset by its own subtly different turbulence and every person had to improvise a way to withstand it. Some of those interviewed seemed to abandon all faith in institutions, while others decided to trust institutions more. . . . A nonprofit worker confessed, 'I used to think that we lived in a society, and I thought that people would come together to take care of one another, and I don't think that anymore.' The archives makes clear that, with respect to Covid--with respect to so much--we are a society of anecdotes without a narrative. . . . Even only three years later, it's jarring to access the first moments of the pandemic in such granular detail and panoramic breadth. You notice how quickly horrendous things became ordinary. One paramedic describes getting called out on 13 cardiac arrests on a single day for the first time in her career and crying on the way home. . . . A nurse is shocked to see a 14-year-old girl, admitted with difficulty breathing, decline so rapidly that, within 30 minutes, she has to be intubated and moved to the ICU. And yet, it was the look of horror on the face of the girl's mother that truly undid the nurse."

"One woman who worked in the art world said: 'It just feels like everybody is in, like, different levels of hysteria and stress and anxiety constantly.' . . . A man surprises himself by how ferociously he screams at another dog owner . . . 'I don't think I would have been as incensed if there wasn't the larger cloud of existential dread hanging above our heads.' . . . 'Relationships of care--close relationships--have deepened. But at the same time, the outer rings of the social world feel hostile.'"

"Our individual identities depend on the frameworks in which we're embedded. But during this first act of the pandemic, the entire theater in which many people gave those performances crumbled. . . . a 'socio-material crisis': a breakdown in the predictability of the material world around you. . . . And without any sense of when the pandemic would end, it became impossible to break out of that malaise, to project oneself into a future that kept evaporating ahead of you."

"The scale is upset, but a new scale cannot be immediately improvised. . . . The limits are unknown between the possible and the impossible. . . . There was hunger for any frame of reference. . . . With few applicable norms in sight for navigating daily life, everyone had to work up individual arsenals of rules from scratch. There were complex moral questions to settle. . . . Sociology makes you aware, in a systematic way, of the power of the society we're embedded in, rather than seeing the world as an archipelago of individuals, the way economists and U.S. culture generally want to make you see things."

"In big ways, in small ways--in ways we may have stopped even registering as bizarre--facets of our society are most likely still trapped inside little, broken flow charts, knocking helplessly back and forth, even now. . . . While the pandemic created widespread pain and vulnerability, it also made existing pain and vulnerability more visible--others' and our own. it was as though, in normal life, we knew to brush that discomfort off."

"At first, the pandemic seemed to create potential for some big and benevolent restructuring of American life. But it mostly didn't happen. . . . 'We didn't strive to change society. We strived to get through our day.' Marooned in anomie and instability, we built little, rickety bridges to some other, slightly more stable place. 'It's amazing that something this dramatic could happen, with well over a million people dead and a public health threat of massive proportions, and it really didn't make all that much difference.' . . . Over time, we simply stirred the virus in with all the other forms of disorder and dysfunction we live with--problems that appear to be acceptable because they merely inconvenience some large portion of people, even as they devastate others. If this makes you uneasy, maybe it's only because, with Covid, we are able to see the indecency of that arrangement clearly."

No comments:

Post a Comment