Occasionally we actually get some good ideas from PD in-servicing. I previously wrote in praise of Paul Gorski's anti-grit (possibly now anti-resilience) stance. Today we watched a video that, in a nutshell, asked us to better understand how stats work, which is a very necessary concept for everyone to grasp in order to recognize that the average of a group isn't reflective of each individual. The more interesting bit here, though, is instead of teachers differentiating instruction for each student, we might be able to teach students to figure out what they need to be their best learners, I think possibly by offering weighted options, challenging them to adhere to time limits, and helping them figure out the difference between true limitations and failures due to educational barriers. This is a bit round-about, but it all comes together in the end.

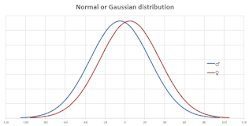

In my social science classes, I belabour the implications of population data falling on a normal curve. What we take as "normal" is typically just 68% of the population, and the other 32% is... something else. If we can really wrap our heads around this idea that only 68% will be one standard deviation from the norm, then we can better understand how stereotypes form, and how terribly simplistic and inaccurate they are as a way of understanding any group of people, thus beginning to dismantle prejudices and discrimination.

I also discuss how much different populations overlap, so even though the average man is taller than the average woman, which is

true, we can all call to mind many examples of women we know who are taller than men we know because the average doesn't tell the

whole truth. The take-away is that we can never extrapolate information about a group to better understand an

individual within that group! Somehow we completely forget this when people talk about personality traits, like being nurturing, aggressive, or efficient. Or

horny! There

are differences between groups divided by gender or age, on average, but there are always far more differences

within each group than

between the groups. I remember learning that concept in grade school!

What today's PD discussed is a shift from focusing on accommodating the average student, towards focusing on the

range of abilities in the room. We watched

this clip from 2018 about a book,

The End of Average, written in 2016 (reviewed

here). It's not a new concept - at all. But what I particularly liked about the clip was this one throw-away line:

"We talk all the time about growth mindset, student agency, self-regulation of learning, and I realized that this is it! This is what we're talking about: How do we teach students to make the adjustments that they need."

I love the idea of getting kids to learn to choose what works for them instead of putting the onus entirely on teachers to adjust the curriculum to meet the needs of each student. If we can do that part well, actually point out to kids their individual barriers and what might work better for them so that they can make informed choices about how to approach a lesson, that might be a game-changer! I also like that it puts something back on kids to step up to the plate instead of all the work and blame being entirely on teachers. As a student, my mum would admonish me to either learn from my teachers or in spite of them, but it was up to me to make sure I was getting a good education. We've lost that message over the years.

HOW TO GET KIDS TO ADJUST WHAT THEY NEED

But how and when do we teach kids about how they work best? Right now, some students bring up their learning style to me, and I have to let them know that learning styles

were debunked as junk science ages ago. We gravitate to the simple over the complex, but how people best learn is

extremely complex. It's not just different from person to person, but can be radically different for

each person as they approach different subjects or types of assignments or even just as they mature.

The other things students have jumped on is the "tests don't measure learning" bandwagon. I don't buy it. Memory of information is crucial to

learning information. There

is significant research on the benefits of

spaced repetition: reviewing concepts daily, then weekly, then monthly, then at the end of the course, accumulating ideas together with increasing complexity as we go. Sure we can get them to play games to review ideas, but testing provokes

students to get in the habit of regularly reviewing their studies. That's important, and it seems to be getting left being in our project-based learning kick. And students don't love it because review can be tedious, despite being effective, but we can't reinforce their desire to be perpetually entertained. Learning to do boring work is a vital skill. Here's the thing, though: tests are important, but they can't be

all that's important. I

do agree that a test, on its own, isn't a good assessment of understanding. But let's not thrown the baby out with the bathwater.

But

can we get all students to succeed at the highest level? (And for what

purpose since universities can only accept about 30% of the population anyway, but more

on that issue here.)

MILD, MEDIUM, and SPICY

When destreaming, we're asked to divide questions into three ability levels, then get students to try the questions at each level. All students are encouraged to at least try some questions in the spicy category. I asked a math teacher, "But what happens if a student can only do the mild questions?" More specifically: "If a student does really well on mild questions, but can't do the medium or spicy questions, what mark will they likely end up with?" The answer was 59%. If they can only do the lowest level questions, it was explained to me, then they can't get more than a level one on their report card. So, even though we're destreaming, it seems like the mild, medium, and spicy categories keep things somewhat streamed within the classroom with just a change of name away from Fast Forward, Applied, and Academic. It's like calling a swimming level "tadpoles" instead of "beginners." But maybe I'm completely misunderstanding it, since I don't teach math. The point, I take it, is that the kids who would formerly be in a class of other mild-question-answering kids, now have the opportunity to try more spicy questions. My concern, however, is that instead of being able to reach a level 4 in a mild class, they'll sit at a level 1 in the mixed salsa class, which can feel pretty crappy.

But here's a different issue. In my classes, it's not really possible to objectively judge which is easier, either by question or by assessment, e.g. a writing assignment, quiz, or participation. I might suggest that an essay is hardest and participation is easiest, but someone in the room might find the reverse to be true. It's the problem I have with Bloom's taxonomy that ranks remembering details lower than connecting ideas. I've always thought that order should be flipped because I can get the big picture far easier than noticing details. It's easier for me. In a philosophy class, what possibly counts as a spicy question compared to a mild question in a way that the spicy question is necessarily more challenging for all different types of thinkers? It might seem that, "Who wrote The Meditations?" would be objectively easier than, "Explain The Meditations," but that's definitely not the case for some kids.

TYPOLOGY FOR DIFFERENTIATION

And then I tweaked on to something, and this is going to sound really out there, but bare with me: Those two different perspectives - big picture vs details - fit nicely with Jung's typology as intuitive vs sensing. Only a quarter of people are intuitive (big picture), SO it might not be the case that connections are a higher order way of thinking, as Bloom suggests, but that they're a different way of thinking that happens to be less common. Because fewer people can do it easily, it might seem more difficult. As we move up the grades in school, typically we shift from detail question (what happened) to big picture questions (why did it happen). In lower grades, I looked like a moron because I couldn't remember the main character's name in the book we were studying. But once we started thinking about books more broadly, looking at theme and connections, then I could finally shine when others didn't get how I got the answers. It's not that I suddenly got smarter; it's that I was suddenly asked the questions I could answer. It's just a different way of thinking that is more rewarded in some settings than others. And it's rewarded more in higher grades because people mistakenly believe we develop this way of understanding as we mature instead of the possibility that some people just have it and others don't, likely the same people who think it's pointless to teach philosophy in grade schools (despite it being a brilliant idea)!

The problem here is the concept of "higher-order thinking." Thinking just is what it is, and people who don't get the big picture, but are solid on details, are clearly pretty useful to the world too, right!!

Is it possible for all ways of thinking to be equally rewarded in the classroom?

If we stick with Jung's typology as a starting point that loosely, albeit questionably, divides people into modes of perception on different continuums, then we need options for introverts instead of mandating group work, which might look like options for chatting with others OR quiet reflection. We could offer detailed questions OR questions that are more open-ended. We could have questions that can be done in a mechanistic way - learn a bit then do a task on it OR projects that last a few weeks at a time. We could mark notebooks to acknowledge the types who maintain them like a work of art OR let them produce a satisfying mess of ideas tied together with string or easily accessible straight from their brain! (I had the neatest notebooks because my brain can't hold a thing without it being in writing, and I'm jealous of people who don't have to write anything down!) We can offer a choice of assessments demanding a block of concentration OR in chunks; a choice of juggling many projects at once OR intense focus on one thing.

OR we can continue doing what many of us currently do, which is to offer it

all, and make everyone do a

little of the things that don't suit them because we all know the benefits of

diving into our weakest areas. Check out that link to see how measuring a swim meet by

finishing it, instead of by time, affects willingness to be challenged. Everyone has to try every task, but it's cool if they're not great at them or don't get as far as others. But, what I add to that, which I think addresses today's video and my concerns above, is to then weigh their assessment heavily towards what

does suit them - what they can do

best to demonstrate understanding.

WEIGHTED OPTIONS

In my classes, I give quizzes and tests and an exam, even though we're told not to have exams anymore. Everything counts for marks, BUT I weigh everything they do in order to get the best possible picture of how much they understand. I assess near-daily understanding through reflection journals where they can apply the concepts, and then they can put the ideas together at the end of each unit in a writing project to get one more chance to practice and get feedback before they tackle the test. I've also had students over the years who don't put anything in writing, but their participation makes it crystal clear that they understand the concepts beautifully. We

all have,

right? So I also assess comments in class. My marksheet for each student looks something like this (full

marksheet here.):

In this particular class, I weigh Response Journals, Writing Projects, Quizzes, and Discussion out of 10, 20, 30, or 40, based on which is their highest mark. So kids who never participate, can only lose 1% in total if the unit is worth 10%. Students who only participate, can almost pass without doing much else, and I can modify the weighting whenever it makes sense to do so! Their final assessments in the course only count if they improve their mark, so students are motivated to get the marks they want during the term and then relax at the end. Students who take a while to catch on have that final opportunity to demonstrate their understanding in the course. It doesn't make sense to me not to provide an exam for students who finally get what we're doing. It often raises their mark!

ON TIMING THEM

We were told today that every test should allow for double time, so if we give them 75 minutes to complete a task, it should take most students 37.5 minutes. But, why?? I've found that the more time I give student to do work, the longer they take to do it. The test that we cut in half this year to take 37.5 minutes, will need to be cut in half within a few years because they will slow down to fit the time limits. Time, money, and counter space are similar in that the more we have, the more we use for junk, so we're wise to be cautious about thinking we need more and more. I used to have kids write an essay as part of an exam, but now they can only manage some multiple choice and short answer questions in the same duration. We're not teaching them how to think and work efficiently, but, I fear, we're instead accepting that their attention span, weakened from social media use, has impaired their ability to think clearly on the spot. Instead of working on getting them to be 'on' and focus their thoughts to get ideas on paper, it feels like we're just accepting that they'll never be able to do this!! Instead, I get them to practice doing more and more in a limited time period, the exact opposite of what we were told to do today.

With projects, I give due dates, but students can easily email for an extension to set their own due dates provided they ask before the original due date passes. That works really well for everyone, spacing out my marking for me over a week, and teaching them to be responsible for their own workload and to learn about their own abilities. But to get them thinking and focusing in an efficient manner, I do "Timed Writings": I give them an hour to write on a topic we've been discussing, and they have to write for the entire hour. It can't be a perfected piece of work, so they have to let go of that and just get their thoughts down in a, more-or-less, organized fashion, recognizing that they might have to stop mid-sentence. They claim to like doing them!! It's not stressful because they're not assessed on length or spelling; I just want to see how well they can talk about the ideas we've been discussing. But more important, it shows them that they can work under a time constraint.

SO, HOW DO KIDS ADJUST WHAT THEY NEED??

These concepts that measure a variety of ways of perceiving, understanding, and demonstrating learning might be able to address students who could do the work once closed doors were opened for them by recognizing how they learn, but it might (likely) have little effect on each of us as we try to push the limits of what we're able to understand. I can finally answer those big questions in English class, but nothing enables me to think fast enough for team sports in phys ed or to get a handle on grade 13 physics beyond the mild questions, or at least nothing that would have been worth the time investment, which would have taken over all other courses to little benefit. It's good that we all have some limitations, though, because it helps us better appreciate our need to live in a community with one another! The trick is figuring out which limits can be overcome with some relatively simple adjustments, like a cheat sheet or extended time (or a firm deadline), and which to accept.

The other component missing from this is that, instead of just assessing the understanding of the curriculum, students could be prompted to notice what works well for them and what doesn't in each classroom, and track it over the years, recognizing that it will likely differ from course to course and as they age, but specifically looking for what works, not what needs to be improved.

It might

seem like we do this when we get students to track

work habits, but that feels like a guilt-inducing practice asking kids where they sit, from excellent to unsatisfactory, on measures that might be largely out of their control: like how well they

collaborate in assigned groups or how organized they are. The better I understand the genetic nature of

executive functioning, the less I think we should be measuring how well kids stack up like this. It's like assessing how well they can see or hear and giving an E, G, S, or N on sight or hearing, making people like me, who can't read these words unaided, feel like I've done something wrong or that I somehow just suck at school, instead of

addressing any barriers in order to carve the clearest path towards optimal learning.

Instead of focusing on improving habits, if we give them many options within each class and among different classes, which most of us do already, and we provoke them to track when they do their best work, and get them to really notice what they think affected their successes and failures, then they might better come up with an ideas of how they really learn best in similar situation. For instance, while most people do better work in quiet, some kids, the ones not in the "normal" range for this particular trait, do better with lots of noise around them. That's where understanding range over averages comes in. Each student needs to figure out where they fit on all the various aspects that affect their ability to learn as best as possible. Then it won't be a matter of the teacher providing the right tools, but the students each bringing the tools they need to the table whether they're attempting the mild or spicy questions. Teachers will merely have to learn to acknowledge the whole enchilada of tools in the toolbox (you knew that was coming!).

And then, in the PD meeting, some vague comments were made about this image:

I wrote about this image

NINE years ago, where I said something similar to here, establishing the importance of accepting our limitations while working to reach our potential:

"Students need to be guided through failure - to be given work just a bit above their abilities to give them enough of a challenge that they learn to be persistent. . . . It's an odd belief that if the kids can all get high marks, or pass without effort, then they'll stay in school. Kids know when they're getting something for nothing and they lose all respect for teachers that cater to them. They want to do work they can be legitimately proud of. . . . Students should be treated fairly, which means evaluating them against the same established criterion for each course. If the measuring stick moves with each student, then it no longer measures anything accurately. We can't all be 6' tall - and there's nothing wrong if we're not. It's curious that we want to celebrate difference in every arena except academically. [BUT the problem is when someone

is 6' tall, but has been crammed into a smaller box so long that they don't know

how to stretch out to their full size.] . . . My classes get myriad options of topics and a chance to display a

variety of skills to show they've learned something within each unit. They can expand their knowledge in limitless ways showing off their talents along the way."

Plus ça change...

When AER first came in, about then, I had a very bright student who commented that it was the first year he got good marks in school because he usually lost 40-60% of his mark to late deductions. That's the best part of Growing Success and AER, forcing us to make sure that policy never gets in the way of potential. But we have to be aware that some extrapolations of the main ideas, like longer and longer timelines for test, can provide diminishing returns and actually impair learning.

Today I was supposed to complete a survey about what I learned to assess my own learning, but I don't think a list of standard questions would provoke my best work, so I wrote this post instead. It helped, dramatically, that we were able to work from home because it's a snow day today. These little accommodations can go a long way! I'm excited for the day that admin actually walks the walk with every not-so-new-and-improved pedagogy they suggest!

No comments:

Post a Comment