This will be a long one, but I'll break it into headings (after this preamble) for easier bit-at-a-time reading!

There's a division among school board trustees and some parents around the best way to tackle discrimination to ensure the best outcome for students and society. The board currently has been providing anti-racism education to staff, and many teachers discuss discrimination in various ways in their classrooms, but now we're seeing some backlash against these policies. It's happening in other boards as well, and it's starting to feel like an organized movement. Taking the most charitable view possible of the backlash, which is at various times part of the "FAIR" movement, anti-CRT (critical race theory), anti-anti-racism, and/or anti-2SLGBTQ+ books in the library, those opposing anti-racism education might be well-meaning and don't necessarily harbour racist or homophobic/transphobic views at all, but they have a different solution to discrimination than is currently outlined by the board. Remember that's the most charitable perception of this perspective. From what I've seen so far, however, their solution hasn't been overtly described, so I've been left to piece together that they're hoping to end discrimination by no longer discussing it. That summation might be in error, so I'm open to hearing a more comprehensive plan of action.

If it is an accurate summary of their stance, then here are the two positions we're exploring in our goal to reduce discrimination and dismantle roadblocks for marginalized groups:

- Anti-Racism Education: Educate teachers on implicit bias to ensure fair treatment of students and assessments in the classroom, and educate students on implicit bias as well as systemic discrimination and intersectionality to help them understand how some people are able to get further in their field with less effort and mitigate those embedded structural components.

- FAIR: Stop discussing CRT, privilege, intersectionality or discrimination in order to help all students feel equal.

If my understanding of their solution is accurate, that we shouldn't discuss racism in the classroom or allow access to books about trans experiences or same sex unions in our schools, then that makes about as much sense to me as hoping to decrease pregnancy rates by not talking to kids about sex -- or, a more current example, as much sense as hoping to end Covid transmission by claiming it's over and removing all protective measures. Some anti-CRT delegates have attempted to show evidence that our current practices don't work, but I've seen no research suggesting that just ignoring it all has a remotely positive effect. To change paths we'd need to see that talking to kids about these issues, also known as educating them, is detrimental, and that staying silent is beneficial.

My concern is that pretending that racism and homophobia and transphobia and same sex marriages, and trans experiences don't exist, a lack of education on these issues, will increase discrimination over time from creating a fear of the unknown and just plain ignorance. The idea that prejudices are alleviated through knowledge has been with us for decades if not centuries, so this recent challenge to that understanding has provoked eye-rolling and exasperation instead of a thorough exploration. On top of that, CRT on its own is a bit of an American far right dogwhistle, which is what, I believe, led the board to avoid the topic, understandably, instead of doing a deep dive.

But let's actually take a look! (That was just the preamble!)

Table of Contents:

Some Useful Definitions and Explanations

Studies on Anti-Racist Education That Show Benefits:

How We Discuss Prejudice is Important

Professor David Millard Haskell's Presentation

Bill 67: Racial Equity in the Education System Act

FAIR: Foundation Against Racism and Intolerance

Some Useful Definitions and Explanations:

Here are some definitions with examples in the simplest wording to help people understand that these aren't scary terms:

CRT / Critical Race Theory: Here's an explanation from @KojoKoram, Birkbeck law professor:

"CRT emerged out of Harvard law in the 80s in an attempt to explain the contradictions between the legal equality achieved through the civil rights struggle and the ongoing visible difference in the impact of the law across racial groups. . . . Look at your prisons. If law is blind, why does property law, criminal law, etc. seem to punish some groups more than others? . . . If your explanation for this is anything other than 'Blacks are just naturally/culturally more criminal' . . . then congratulations, you have just started doing CRT."

It's taught as a very minor part of the curriculum in two courses in our board, always alongside many other theories as another example of a possible perspective to take to understand society.

And it's also part of an AQ course (Additional Qualifications) that's optional for teachers:

Note that both of these documents are created and directed by the Ministry of Education, not individual school boards. It's not under the jurisdiction of school boards to remove CRT from curriculum.White Privilege: This is an idea that gained traction in the 1980s with Peggy McIntosh's article, "White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack," which lists 50 different subtle things that affect people like "I can turn on the TV and see people of my race widely represented." It simply a way to understand that some people have barriers to success that previously went unacknowledged.

Intersectionality: This just means that different aspects of our lives intersect, and when those aspects are seen as part of a subordinate group, then those intersections add up to more difficulties accessing jobs, housing, basic respect, etc. For example, someone impoverished who is also Black, queer and visibly disabled will likely face more barriers in life than someone impoverished but White, straight and visibly able-bodied. So while it's definitely the case that someone who's White and living below the poverty line is struggling in a way that shouldn't happen in our society, it's even more difficult for people who also have additional aspects.

Implicit Bias: We've picked up ideas from our culture that some groups are better or more important than others, and we tend to act on these faulty assumptions when we're unaware of them. I learned about this in the 80s when studies showed that teachers call on boys more than girls to the point that girls stop raising their hands. Once aware of that, I started tracking my hand-calling to make sure I heard from everyone. That's it!

Systemic Discrimination: This is tied to implicit bias in that discrimination often isn't a conscious thing we do. It's sneaky. I didn't believe this until I worked in an insurance company that was 70% female, but 95% of bosses were male. I watched a new guy in our department get invited to lunch and golf by the bosses, and realized that the system was rigged against women. It's not that these bosses were bad people, but that people naturally want to promote others who are similar to them, and, because of blatant discrimination over the years, we've started with most of those in power being straight white able-bodied men, creating a perpetuation of straight white able-bodied men being offered more supports than others.

Studies on Anti-Racist Education That Show Benefits:

We can look to American schools that have accepted this anti-CRT perspective as some states drafted laws designed to limit the teaching of what some call "critical race theory" (but typically mean implicit and systemic racism). A recent Scientific American article said that there's "an ever growing body of scientific evidence that suggests these laws are failing the children they purport to help." Implicit racism exists from an early age--they cite 4-year-olds pairing white children with higher-wealth items, and stereotypes starting at age 6--so it's only through talking about it that we can decrease discrimination. Children notice the difference between groups, such as white people being wealthier, so they "need external explanations, such as historical injustices and racial discrimination, to understand the differences between groups that they are observing. Without that context, children can mistakenly believe that racial difference is inherent, which leaves them with an inaccurate understanding of the world." If racialized kids believe white people are wealthier because somehow white people are smarter, instead of just having an easier time because of systemic discrimination, then that belief can deflate potential aspirations.

"The research we've discussed suggests that students will be more likely to develop racially biased views in the absence of explicit lessons. By contrast, having explicit conversations with kids about racial disparities can help reduce some of the negative consequences we have described. In one study, white elementary school students who received history lessons about racial discrimination faced by African Americans had more positive views of African Americans and were less likely to hold stereotypes than students who didn't receive such lessons. Importantly, those lessons did not lead either white or Black children to hold more negative views of white Americans, which is a commonly voiced concern among those who oppose teaching about racism."

There's also evidence that honest, accurate conversations about race can decrease kids' racial biases in homes even when parents are uncomfortable with the conversations. The study concludes, "When it comes to children's understanding of racism and the development of racist beliefs, the biggest danger isn't teaching or talking to children about these topics--it's staying quiet."

Another study found that a 10-minute non-confrontational conversation in which people are put in the shoes of trans people in order to understand their problems significantly reduced transphobia immediately and the change lasted at least three months.

Some researchers think the move to silence discussion led to the suicide of a 10-year-old Black girl as she was taunted by racial slurs: "A continued lack of bystander intervention from her peers or school administrators alike contributed to Izzy committing suicide. Silence and inaction do nothing but cause biased perpetrator behaviors to proliferate as they feel unquestioned." The teacher didn't intervene because of a new law around discussions of racism in the classroom.

Other studies show better overall education when prejudice is discussed. Some researchers "have found that students are more engaged in school after taking classes that frankly discuss racism and bigotry." Another found higher grade point averages in students offered an ethnic studies course. Another study of schools found that discussions about topics like Black history and culture and how to challenge negative stereotypes significantly reduced dropout rates among Black boys. And a class that focused on social justice and patterns of oppression boosted test scores and graduation rates.

Finally, with respect to fostering racial/ethnic identity through clubs at school, a study found that,

"A well-developed racial identity . . . may help a targeted individual distinguish between actions directed at the person as an individual versus those directed at the person as a member of a particular group. This can protect targeted individuals from injuries to self-esteem or distress when they are exposed to negative events that may be a function of ethnic discrimination rather than individual characters of behavior. Ethnic connection and belonging could ameliorate some of the pain of ostracism from other groups. . . . Our review identified 12 published peer-reviewed papers that explicitly tested the hypothesis that ethnic or racial identity buffers the effects of exposure to racism on psychological distress or depression."

Anyone close to my age can likely see from their own experiences that overt racism in schools has diminished. People don't openly point and laugh at differences. Teachers don't use racial slurs regularly in classes like some did when I was in school. When I first started teaching we used to use an old history video in which a teacher in the video called newcomers stupid! Attitudes have shifted for the better because we've started talking openly about racism and teaching anti-racism in our schools.

How We Discuss Prejudice is Important

I wrote previously about concerns with new anti-racism programs in the hands of burgeoning anti-racism educators who aren't quite ready to teach some of the more provocative lessons and possible end up leaving white kids feeling guilty or shameful for being born white. How we teach it is important. Trustee Watson called for an exploration of precisely what teachers are teaching, but she centred it around CRT, so it was voted down. CRT is in our curriculum, which makes that a ministry issue, not a board issue. Discussions of problems with CRT in particular, instead of specific problematic lessons, also might suggest attachment to some extreme far-right groups in the United States, and we should hope we don't want any affiliation with any white nationalist ideologies.

We can't change the curriculum, and it would be difficult to explore every type of teaching from every teacher since some anti-racism lessons are impromptu, sparked by events or questions raised in class by students. However, we can encourage teachers to use greater care when discussing discrimination since that appears to be a concern.

We can teach about discrimination in a very non-confrontational way, without making anyone feel like they're to blame for our entire colonialist history. I discussed this previously with respect to concerns with a 'privilege walk' exercise. We can explain about bias and be open to the reality that we could unfairly judge someone so that we can prevent that behaviour in ourselves. Here are 10 Lessons for Talking about Race that are careful to avoid finger-pointing. We definitely need to discuss CRT and privilege and any words in the zeitgeist that kids have heard and might not quite understand so that they leave high school better educated. It's likely that this anti-CRT movement has unwittingly provoked more discussion of the term. Noam Chomsky said last year (and again here):

"CRT is a cover term for everything the far right doesn't like: women's right, opposition to white supremacy. . . . They demonize it, mobilize parents, tell them schools are forcing children to believe they are oppressors because of their skin colour, and it's working."

"Previously a lot of people had no idea about CRT. Now we have an opportunity to step in to teach about CRT. . . . Look at the right-wing hysteria about CRT. They haven't a clue what it is and don't care; they claim it's a demonic thing run by the radical left to make white kids feel guilty for anything happening. We need to respond by exposing the truth. We're presented with an opportunity to point out what CRT really is and why we should take it seriously. It's not an attack on children or school, but an effort to bring about an understanding of our history and the legacy it has left."

My Own Lessons:

In my HSB4UI course, with grade 12 students about to go to university, we spend several weeks on discrimination and hate crimes. I explain all the foundational and current theories that attempt to explain the origins of prejudices, including a bit on CRT. We come up with lots of examples to illustrate each theory clearly. These are just theories of behaviours, so they are wide open for debate. Most students come to class with some theories under their belt, the most common being modelling. We understand prejudices as something we've seen from parents or peers or media. The more racism is modelled on TV as acceptable or even glorified, the more it's copied and carried out in real life. If we watch an old TV show, we can experience how much our prejudices have been quietly dismantled over the decades when, for instance, a joke's punchline is that women are only good for cooking and sex, and it just fall flat. Jokes are no longer funny when we no longer hold that view in a corner of our mind.

But let's look at the other side - some claims that anti-racism education is harmful.

Professor David Millard Haskell's Presentation

I listened to Professor Haskell's presentation at a WRDSB meeting on the harm caused by anti-racism education live, but re-watched the the video now that I have time to look at all the studies he brought forth as evidence. The short version: I remain unconvinced by his research that anti-racism education is harmful.

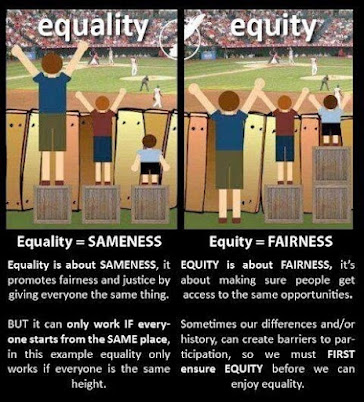

His stance is anti-discrimination and pro-human, and he's a member of FAIR, which I'll get to later. This is a position that typically seeks to have everyone treated equally in a way that ignores current unfair advantages and disadvantages of people, seeking equality over equity:

|

| Interesting origin story of this here. |

"We can disagree and still love each other unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression and denial of my humanity and right to exist."

The Ontario equity and inclusive education strategy focuses on respecting diversity, promoting inclusive education, and identifying and eliminating discriminatory biases, systemic barriers, and power dynamics that limit the ability of students to learn, grow, and contribute to society. Antidiscrimination education continues to be an important and integral component of the strategy.

"Reading about White privilege decreased their sympathy for other challenges some White people endure (e.g. poverty). . . . We conclude that, among social liberals, White privilege lessons may increase beliefs that poor White people have failed to take advantage of their racial privilege--leading to negative social evaluations."

"If you're going to talk about white privilege, then it needs to be explicitly said that this doesn't mean that white people don't have individual struggles. . . . If we can recognize these nuances, then it might help us to feel more empathy for everyone."

"There are very real racial inequities in society today. Choosing language that promotes constructive conversations will not solve those problems. But it is an important step toward collectively understanding their dimensions and working together toward a solution."

"A collection of interventions that on average produce effects of .357 is certainly meaningful. The problem is, can we believe that the average effect is 0.357? The evidence reviewed above suggests that we cannot."

"It's more effective to engage managers in solving the problem, increase their on-the-job contact with female and minority workers, and promote social accountability--the desire to look fair-minded."

Also brought into question by anti-CRT advocates in Ontario, is Bill 67, which passed the second reading last March with a vote of 72 to 1 (only Belinda Karahalios of the New Blue Party opposed it), and will be brought forth again by Laura Mae Lindo. It has to do with making school boards responsible for spreading anti-racism ideals. Racism is defined as justifying or supporting "the notion that one race is superior to another." The goal of anti-racism education policy is to end the propagation of any conception of a superior race. I'm baffled that this is controversial! Here are some of the policies:

- training for all teachers and other staff

- resources to support pupils, teachers and staff who have been targeted by racism

- strategies to support pupils, teachers and staff who witness incidents of racism

- resources to support pupils, teachers and staff who have engaged in racist behaviours

- procedures that allow pupils, teachers and staff to report incidents of racism safely and in a way that minimizes the possibility of reprisal

- procedures that allow parents and guardians and other persons to report incidents of racism

Color-awareness advocates argue that "racial justice and colorblindness are not the same thing. Race-neutral policies are only as good or bad as the results they produce. . . . To assume that ignoring race in making social policy will bring about justice or achieve morality is legal fantasy." Moreover, people of color may not want to be treated as raceless or colorless, since so much of who they are is the result of growing up as a person of color in America. To "e-race" individuals is to deny them a meaningful identity and separate them from their own flesh and blood. Adoption of a colorblind approach would permit society in general and courts in particular to avoid accounting for and grappling with fundamental issues raised by past and present discrimination. Color-awareness, rather than sidestepping theses issues, posits that it is permissible and desirable to take race and color into account when remedying the present effects of past racial discrimination.

FAIR: If we tell kids that their success or failure is a matter of skin colour, then they'll be discouraged and give up. "Psychologists call this learned helplessness."

Dr. King's line about not judging his children "by the color of their skin but by the content of their character" is too often shamefully applied to argue against affirmative action or any race-based remedy to historical injustice. But the "I Have a Dream" speech itself contradicts this in his bold call for fighting the fight "until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream." Moreover, his public views before and after this speech included support of the Indian government's special employment opportunities provided to the caste formally referred to as untouchables as a remedy for these discrimination victims, social reforms for African Americans similar to the G.I. Bill, and a call for "massive" preparations that were bold, but "less expensive than any computation based on two centuries of unpaid wages and accumulated interest." In essence, Dr. King's argument is not to be color blind, but to be color kind.

King decried both the continuing "withering injustice" of slavery and its contemporary impact. He also spoke of the victimization of Black people by police. His legacy calls for leaders to stand before nonracialized communities to lance the fear forged in ignorance. . . . Martin Luther King Jr. did not advocate colour-blind politics. He was consistent and specific that his work was grounded in the lived reality of the injustices faced by Black people and sought solutions that reflected an understanding of racism's transgenerational impact. He worked in coalition with others when they shared his goals, but he was not an apologist who sought to make white people comfortable in their racism. He viewed redress as an urgent matter. King called for immediate action and cautioned against "the tranquilizing drug of gradualism."

"If I had a pound for every time a Tory MP of colour has been wheeled out following government charges of discrimination, or indifference towards tackling racism and/or improving inclusion...."

1 comment:

Post a Comment