Someone told me that we need to adapt to Covid faster, and get used to masks and checking air quality much faster for our own survival. They think our problem is our inability to adapt to this new environment. I said that I think we have adapted quickly, but we've done it in the other direction: we've acclimatized to accept that we will know people who have died at a young age or who haven't been able to get out of bed in months. We've adapted to the turmoil instead of the preventative measures.

Then I came across a thread by Professor Debra Caplan in the U.S. She commented on the lack of films and books on the Spanish flu relative to all that was written about World War I despite the flu taking about six times as many lives in the United States. There are a couple episodes in Downton Abbey. Then there's this 24 min. NFB film, The Last Days of Okak, but she's got a point: so many post-WWI movies that discuss the ravages of war don't mention a thing about the devastation caused by the flu.

I wonder if it's that our brain processes information differently when it's big and fast instead of long and slow. Is it like the difference between jumping in to help after a Tsunami that kills 2,000 and doing relatively little during an on-going drought that's taking 2,000 each week? It could be the same reason we don't instinctively react to climate change. We're the frogs in the water heated so gradually it's imperceptible, giving us the sense that it's not that big of a deal and we have tons of time to do something about it. So we just go on about our business, complacent. Even the disfiguring monkeypox isn't getting much of a rise out of people. We've got depleted reserves of concern.

BUT, then Caplan goes on to list the many many stories written about previous plagues:

"Prior to the 1918 pandemic, people regularly memorialized plagues in literature. There are countless examples of people using storytelling to process the costs of mass disease. Homer. Sophocles' Oedipus the King. The Decameron. Daniel Defoe's A Journal of the Plague Year. Coping with plague and disease is a major theme of classical and early modern literature. Edgar Allen Poe's The Masque of the Red Death. Jack London's The Scarlet Plague. And so on. It's a stark contrast with the almost-total absence of literature, film, or other storytelling about the 1918 pandemic. What changed? Mass media."

I teach how a few key books fostered the idea that the masses are easily manipulated, and it's the role of media and government to guide them, starting perhaps with Gustave Le Bon's The Crowd, in 1895, in which he argued that people want to conform, so leaders need to tell them what to conform to. Then Walter Lippmann wrote Public Opinion in 1922, stating that the "masses are a bewildered herd that need to be governed by a specialized class." And on to Freud's nephew, Edward Bernays, who took his uncle's idea that we have a natural aggression that needs to be channeled, and profited off channelling it into shopping to get people arguing over the best shoes instead of the best government. He wrote Propaganda selling it like it's a good thing: Consumerism is necessary to pacify the masses and distract them from what happens behind the scenes. So was it someone's choice to have us forget about the pandemic while we're in the middle of it all? Did everyone notice that at the Ontario leadership debate all the candidates spoke of Covid in the past tense??

Caplan explains further:

"In 1918, there were vested interests intent on people NOT telling stories about the pandemic because it might affect the war. Information about the pandemic was actively suppressed by most governments around the world, with the exception of Spain (hence 'Spanish flu'). How can you tell a story about something that isn't being acknowledged as really happening? How can you process the pain and loss of a mass health catastrophe in an environment where those in power keep telling the public that everything is fine and normal? You can't, and you don't. So you don't write books about it; you don't make movies about it; you don't use the storytelling tools that humanity has used for centuries to process threats of contagion. You just hunker down and write and watch books and movies about a world where there never was a pandemic or a world where it's over, and move on. No memorials. No moments of silence. No iconic movies or books. Just 'normalcy' and silence.

Back in 2020, it was inconceivable to me that the 1918 pandemic was ever so 'forgotten.' But now, it makes perfect sense. As a society, we're collectively doing our damndest to forget this one too. Even as it's raging on and people are dying. We urgently need to tell the story of what happened - and what's still happening - in this pandemic. We need to publicly grieve the 1 million Americans we lost, and make plans to try to prevent any more casualties. We need to tell the stories of Long Haulers and survivors. Or, we could just choose to forget and hope that things really will feel 'normal' eventually, if we're lucky."

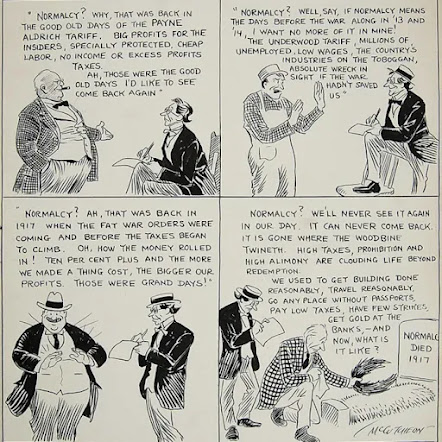

In 1920, Warren G. Harding ran his presidential campaign using the slogan, "Return to normalcy!" This cartoon came out the following year, after he won by a landslide.

2 comments:

Don't think the USA suffered as much as many other countries around the world did from the 1918 to 1920 Great Flu Epidemic. So what happened in their Congress regarding funding to study the germ is of little value to everyone else.

The US wasn't the hegemon it is or claims to be now, so who cares what they thought and did or didn't do back then? Mencken satirized their rubbish politics very well. They also claimed to have won WW1 after turning up literally at the last moment and taking all the credit. That was followed by Wilson the racist US Jim Crow prez waltzing around flaunting his 14 points which the other winning combatants let him do, as it suited their political purposes. I was born in England just after WW2 and it was a common thing to denigrate Americans as blowhards when I was a child. My maternal grandfather who served in WW1 in the Army and somehow survived was decidedly not a fan of America.

Of course, when our family moved to Canada in the late '50s, we then got subjected like all Canadians to constant US media bombardment by magazines and TV. And you'd think nowhere else existed the way they carry on. To me, your piece reflects that Americanization we get ingrained into our souls here in Canada, written by Yankees as if nowhere else matters. The Americans are navel-gazers nonpareil and used to demand complete loyalty from immigrants so they'd not dwell on their roots too much.

So I guess the question is, is the literature of other countries as absent on the flu pandemic as America's is? I don't know. Do you?

If one reads Orwell's outstanding novels and non-fiction, and I'm about two-thirds of my way through, the novel Coming Up For Air is rather wonderful, and encompasses the idyllic days pre WW1 when things never seemed to change, through the war and up to 1938. Much more cleverly written than that cartoon pre and post 1917. The flu gets scant mention from Orwell, so one presumes it didn't affect British society as much as the war itself did. Best book I've read in ages, loved every page, far better than the flawed 1984 which never rang true to my technically-oriented self -- too many loose ends.

Just now, reading the ever-popular and oh-so-reliable Wikipedia entry on the Spanish flu, it seems that India got hit the hardest, the US among the least hard. Maybe India's literature reflects this, but I doubt it. As my paternal grandfather was a Colonial Office university educator in India all during WW1 and up till partition in 1947 when he was in charge of the entire Punjab's education, it's likely from what I heard that NO native literature that could in any way be interpreted as anti-British was allowed or published.

Anyway, I'm unsure whether your premise about the lack of literature on that Spanish flu epidemic is endemic only to the Anglo Saxon world or not.

It's definitely an American take on it, and Caplan's a theatre prof not world history, but I'm interested in the situation within that context. What made a group of people NOT speak of something that must have been a huge part of their lives? And, similarly, how are so many going about their business so breezily in the midst of death and suffering? Even if people don't know someone personally who has died or been significantly ill, surely, with the numbers in the hospital and fatalities we're seeing here, and with the horror show that happened in LTC, they know someone who knows someone who was directly affected. How are we so complacent in the middle of it all? Maybe it's more due to it being a long, slow event instead of due to media manipulation by elites in power. But the messaging coming from the top has definitely had an effect on how we're thinking about this situation: minimize the results and then go out to spend your money!

I wonder if monkeypox will provoke people to wear masks again. I quit smoking in my early 20s, NOT because of any health concerns since, at that point in my life, I was immortal in my own mind. The last straw for me was a poster of a woman with pucker wrinkles around her mouth - yuck! For some people, health is too abstract, but disfigurement is real. I heard today that NS is removing mask mandates starting the 24th - with just one month left of school - and with 17 known cases of monkeypox in Canada so far. Nothing makes sense.

Post a Comment