The Agenda has a video with Jonathan Haidt, social psychologist. I watched it with my kids, and we had a good discussion about it. Haidt published a book, The Coddling of the American Mind, with Greg Lukianoff, CEO of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), a few months ago to very mixed reviews. He has a few interesting ideas, but many are rehashed or questionable.

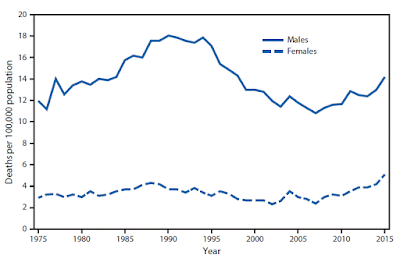

His concern with the iGen or the Gen Z group, anyone born after 1995, is that they grew up with social media, which has messed them up. It's mainly the same story we've already heard about cell phones and helicopter parents. But then he said that boys aren't doing so badly since they mainly play video games and bully physically, but girls are really affected by calls for perfection and psychological bullying that happens more online. My kids jumped on this claim with their own stories, but I cautioned that they just had anecdotal evidence from their own lives, and this guy likely did more thorough research. While it's good to consider how much an idea 'rings true,' we need to evaluate the research. I didn't read the book, but one of the citations is Pinker, which makes me a little bit dubious. Then he said the suicide rate for teen girls has gone up by 70%, but not for boys. One article says the CDC says the rate increased 70% for white youth and 77% for black. The CDC site has this graph, which clarifies how much higher the rate for males is to begin with:

It's not clear from this that Gen Z girls are affected more than boys by social media the way he implies.

Haidt explained the concept of moral dependency, which is a useful term for what's happening. In the 1990s, we started overprotecting kids and making sure they always had an adult nearby to tell in case of a problem. By 2013, kids are over-reporting every potential offence. We grow up by pushing the envelop, and that doesn't happen in children's lives anymore. One trend he pointed out that I have noticed is that kids don't play in mixed aged groups anymore. Parents arrange playdates with kids that are close to their own kid's age. But, he explains, in mixed group, older kids learn to be a bit more gentle and how to lead a group, and younger kids learn to restrain crying or they won't be allowed to play with the big kids. A lot of useful socialization takes place when kids are left to figure things out for themselves. Without that, he suggests, they fall apart when they hit university, and they treat the dean as a surrogate parent.

He makes a useful distinction between political correctness of the past and now. In the 60s, the early 90s, and now, there have been waves of political correctness movements that attempt to develop greater diversity and inclusivity in society, and they've generally been successful. The difference is that previously, if someone were to speak on a racist platform, they'd be protested, and now the claim is more of a concern with people having panic attacks or self-harming at the thought of a speaker in their city. He calls it a "medicalization of the intellectual world." I've seen this change as well, in that a former outrage has turned inward to become a personal attack in a weird way. That's when we suddenly get students asking us not to talk about climate change in class. But Haidt agrees that refusing to discuss it won't help anything.

He says kids today are more anxious because they expect to be "emotionally safe" or else report any concerns. PTSD is very rare and requires treatment, but many students think they have it or will get it through a discussion of taboo topics. But, according to Cognitive Behaviour Therapy techniques, keeping away from reminders of what upsets us isn't a solution, it's part of the problem. I sort of agree with this, except in CBT, people are in control of their own immersion into whatever causes them anxiety. In a classroom, that's not always possible. I think trigger warnings are useful, and they're not a big deal, so long as we're still allowed to discuss the issues. There's never a mass exodus after I say that, for instance, today I might talk about sexual assault at some point, but people in need have a heads up.

But there's another side to this. Haidt subtly implies that students who feel uncomfortable speaking up in class these days are the victims of the PC culture. But I think that dynamic all depends on what they feel uncomfortable saying. If people restrain themselves from saying racist things in class because they know they'll get called on it, that's just basic socialization necessary to any changing society. In some cases at least, people are being pushed to be more respectful of others. And another problem is that we can't just explain away the stress teens are experiencing so easily. There are economic issues today that affect parents' concerns for their kids, which affect their treatment of them.

He says something that I think is a real part of the problem in schools, though: admin must act on concerns, but they don't necessarily have to do anything useful provided they do something! It's a system of accountability instead of a system of compassion. He explains that diversity training doesn't work, but that doesn't matter as long as it's available to be the thing that admin do to ensure they appear to be actively dealing with a problem. Yup. So many wheels spin trying to cover our butts in ways that don't come close to touching the problems.

He has three "great untruths" - which makes it all feel a little self-helpy, but whatever:

1. We need to be protected --> actually we must learn to fend for ourselves.

2. We must trust our feelings --> actually we should question our feelings. A big part of CBT is to catch distorted thought processes and negate them by looking for evidence. We think it's wrong to question anybody's feelings on an issue, but sometimes it's beneficial to all parties.

3. Life's a battle between good and evil --> actually people are all a mix. We're naturally good at intergroup conflict, but also able to turn it down for the benefits of trade. We have to get better at turning down conflict between divisive groups. We can't have an inclusive society if we see people as black and white.

Then he gets a little J.P.-ish in talking about how universities train an ideology that suggests the world is out to get people: that the rich people are all bad and the poor are good. I just wrote about the problems with capitalism where I suggest, not that the rich are bad people at all (although Hedges definitely says that), but that there's a problem with the excesses allowed to the rich at the expense of the poor. I wonder if he thinks that's the same thing. If he does, then how do we explain the problems with capitalism? Or do we?

I do like his final bit of advice to teens: take a few years off before going to university. He says, because of moral dependency, an 18-year-old of today is like a 15-year-old of the 80s. Take a few years off to work and live on your own before going to university or college. He thinks universities should give preference to kids who do that. I've been saying that since we lost grade 13, and kids started going to university before they're old enough to vote. If we can't get grade 13 back, and they're dissuaded from taking a fifth year, then it wouldn't hurt to work for a few years to figure it all out, provided they can find employment, that is.

ETA: It might be helpful to note the complaint about the immaturity of humanity goes back many centuries:

His concern with the iGen or the Gen Z group, anyone born after 1995, is that they grew up with social media, which has messed them up. It's mainly the same story we've already heard about cell phones and helicopter parents. But then he said that boys aren't doing so badly since they mainly play video games and bully physically, but girls are really affected by calls for perfection and psychological bullying that happens more online. My kids jumped on this claim with their own stories, but I cautioned that they just had anecdotal evidence from their own lives, and this guy likely did more thorough research. While it's good to consider how much an idea 'rings true,' we need to evaluate the research. I didn't read the book, but one of the citations is Pinker, which makes me a little bit dubious. Then he said the suicide rate for teen girls has gone up by 70%, but not for boys. One article says the CDC says the rate increased 70% for white youth and 77% for black. The CDC site has this graph, which clarifies how much higher the rate for males is to begin with:

It's not clear from this that Gen Z girls are affected more than boys by social media the way he implies.

Haidt explained the concept of moral dependency, which is a useful term for what's happening. In the 1990s, we started overprotecting kids and making sure they always had an adult nearby to tell in case of a problem. By 2013, kids are over-reporting every potential offence. We grow up by pushing the envelop, and that doesn't happen in children's lives anymore. One trend he pointed out that I have noticed is that kids don't play in mixed aged groups anymore. Parents arrange playdates with kids that are close to their own kid's age. But, he explains, in mixed group, older kids learn to be a bit more gentle and how to lead a group, and younger kids learn to restrain crying or they won't be allowed to play with the big kids. A lot of useful socialization takes place when kids are left to figure things out for themselves. Without that, he suggests, they fall apart when they hit university, and they treat the dean as a surrogate parent.

He makes a useful distinction between political correctness of the past and now. In the 60s, the early 90s, and now, there have been waves of political correctness movements that attempt to develop greater diversity and inclusivity in society, and they've generally been successful. The difference is that previously, if someone were to speak on a racist platform, they'd be protested, and now the claim is more of a concern with people having panic attacks or self-harming at the thought of a speaker in their city. He calls it a "medicalization of the intellectual world." I've seen this change as well, in that a former outrage has turned inward to become a personal attack in a weird way. That's when we suddenly get students asking us not to talk about climate change in class. But Haidt agrees that refusing to discuss it won't help anything.

He says kids today are more anxious because they expect to be "emotionally safe" or else report any concerns. PTSD is very rare and requires treatment, but many students think they have it or will get it through a discussion of taboo topics. But, according to Cognitive Behaviour Therapy techniques, keeping away from reminders of what upsets us isn't a solution, it's part of the problem. I sort of agree with this, except in CBT, people are in control of their own immersion into whatever causes them anxiety. In a classroom, that's not always possible. I think trigger warnings are useful, and they're not a big deal, so long as we're still allowed to discuss the issues. There's never a mass exodus after I say that, for instance, today I might talk about sexual assault at some point, but people in need have a heads up.

But there's another side to this. Haidt subtly implies that students who feel uncomfortable speaking up in class these days are the victims of the PC culture. But I think that dynamic all depends on what they feel uncomfortable saying. If people restrain themselves from saying racist things in class because they know they'll get called on it, that's just basic socialization necessary to any changing society. In some cases at least, people are being pushed to be more respectful of others. And another problem is that we can't just explain away the stress teens are experiencing so easily. There are economic issues today that affect parents' concerns for their kids, which affect their treatment of them.

He says something that I think is a real part of the problem in schools, though: admin must act on concerns, but they don't necessarily have to do anything useful provided they do something! It's a system of accountability instead of a system of compassion. He explains that diversity training doesn't work, but that doesn't matter as long as it's available to be the thing that admin do to ensure they appear to be actively dealing with a problem. Yup. So many wheels spin trying to cover our butts in ways that don't come close to touching the problems.

He has three "great untruths" - which makes it all feel a little self-helpy, but whatever:

1. We need to be protected --> actually we must learn to fend for ourselves.

2. We must trust our feelings --> actually we should question our feelings. A big part of CBT is to catch distorted thought processes and negate them by looking for evidence. We think it's wrong to question anybody's feelings on an issue, but sometimes it's beneficial to all parties.

3. Life's a battle between good and evil --> actually people are all a mix. We're naturally good at intergroup conflict, but also able to turn it down for the benefits of trade. We have to get better at turning down conflict between divisive groups. We can't have an inclusive society if we see people as black and white.

Then he gets a little J.P.-ish in talking about how universities train an ideology that suggests the world is out to get people: that the rich people are all bad and the poor are good. I just wrote about the problems with capitalism where I suggest, not that the rich are bad people at all (although Hedges definitely says that), but that there's a problem with the excesses allowed to the rich at the expense of the poor. I wonder if he thinks that's the same thing. If he does, then how do we explain the problems with capitalism? Or do we?

I do like his final bit of advice to teens: take a few years off before going to university. He says, because of moral dependency, an 18-year-old of today is like a 15-year-old of the 80s. Take a few years off to work and live on your own before going to university or college. He thinks universities should give preference to kids who do that. I've been saying that since we lost grade 13, and kids started going to university before they're old enough to vote. If we can't get grade 13 back, and they're dissuaded from taking a fifth year, then it wouldn't hurt to work for a few years to figure it all out, provided they can find employment, that is.

ETA: It might be helpful to note the complaint about the immaturity of humanity goes back many centuries:

Laziness and cowardice are the reasons why such a large proportion of men, even when nature has long emancipated them from alien guidance, nevertheless gladly remain immature for life. . . . It is so convenient to be immature! If I have a book to have my understanding in place of me, a spiritual adviser to have a conscience for me, a doctor to judge my diet for me, and so on, I need not make any efforts at all. I need not think, so long as I can pay; others will soon enough take the tiresome job over for me. The guardians who have kindly taken upon themselves the work of supervision will soon see to it that by far the largest part of mankind (including the entire fair sex) should consider the step forward to maturity not only as difficult but also as highly dangerous. . . . Thus only a few, by cultivating their own minds, have succeeded in freeing themselves from immaturity and in continuing boldly on their way." (from Kant's What is Enlightenment here)

No comments:

Post a Comment